For all its talk about politics and race, it is unlikely that Jones cared particularly much for either in his fiction work. Before becoming a professional comics creator, Jones publishing a book on comics where he criticized Denny O'Neil and Neal Adam's well thought of tenure on

Green Lantern/Green Arrow, a tenure where O'Neil brought the political and racial conflicts of the day to the forefront in order to give comics what was then termed "relevancy." Jones felt that the title was "ultimately unsatisfying" because "it was hard to believe that the protector of an entire galactic sector could fall apart at the sight of a slum unless, that is, a writer contrived it so." This sentiment expressed itself while Jones was working on the principle

Green Lantern title in September of 1992, when he scripted a scene that made explicit reference to

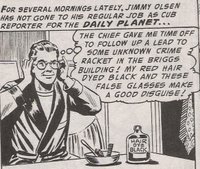

Green Lantern/Green Arrow's most famous scene. In the original Green Lantern meets the indignation of an elderly black man who asks him, "I been readin' about you. . . how you work for the

blue skins. . . and how on a planet someplace you helped out the

orange skins. . . and you done considerable for the

purple skins! Only there's

skins you never bothered with! The

black skins! I want to know. . . how come!?" A shamed face Jordan can only look down and responds hesitantly, "I. . . can't." The mock up retains the same basic composition, but replaces the black man with a blue skinned alien who is given traditional African American facial features. He asks Jordan not what he has done for blacks or other minority groups, but what he has done for aliens. Jordan, seemingly in on the joke, turns not to the alien or the floor, but to the reader and responds, "Now I ask you. . . what am I gonna do?"

The reason why Jones was so reliant on the idiom of the political in Green Lantern: Mosaic was because it was the only tool the genre left at his disposal to transform his work into something that could be deemed literary and himself into what he really wanted to be: a comic book auteur in the mold of Alan Moore and Frank Miller. And although Moore and Miller's mid-1980s work dealt with the political without dealing with race in any concrete way, working within the Green Lantern franchise, John Stewart's race seems like the most obvious way to achieve, what he chided O'Neil for, forced "relevancy." This reluctance to include political material was a times in Stewart's own desire to be more like Hal. In one sequence we catch John reading reprints of 1960s Green Lanterns. A smile on his face betrays a deep satisfaction and the envy that unlike Jordan he can't win his fights by "invoking arcane scientific principles."

No matter how resistant Jones might have been to doing a political book, nonetheless he realized that the politics of the Mosaic was his best opportunity to achieve the artistic status that he desired so fervently in the letter pages. Discussing his time working in a used bookstore, Jones told his audience, "I became more convinced than ever that I would Die in Agony if I did not Become a Writer." Working within the formulaic world of superheroes he needed John in order to not just be a self-described "Hack," just as the usually narratively subordinated John mentions needing the Mosaic world, to find his own voice. Addressing the reader once again, John informs us that, "the courage to use your own voice. That's the test of maturity. That's the proof of seriousness. Maybe that's my mission here. To find my voice."

Of course voice means nothing if you don't have an audience, and it is here where Jones's rhetoric and the form of the comic narrative begin to reinforce each other. An unusual formal device utilized throughout the Mosaic series, particularly given the genre, was to have Stewart speak directly to the audience, convincing the reader of his position and his goals. However, as the series progressed, other characters were allowed to speak directly to the audience and give their point of view. For instance, the issue dealing with the Trendoids begins with a Chicano low rider, announcing his annoyance about the cultural copycats. The issue then follows the low riders until he meets one of Stewart's teenage assistants, who then takes over the narration. However, while they are both capable of speaking for themselves, neither of them are capable of managing the Mosaic. It is only when John takes over the narration in this sequence, that progress is made. While he still allows others to speak, he selects those from the community that he wants to represent and shows his mastery over them on the next page by sitting on top of the images of those talking.

Of course voice means nothing if you don't have an audience, and it is here where Jones's rhetoric and the form of the comic narrative begin to reinforce each other. An unusual formal device utilized throughout the Mosaic series, particularly given the genre, was to have Stewart speak directly to the audience, convincing the reader of his position and his goals. However, as the series progressed, other characters were allowed to speak directly to the audience and give their point of view. For instance, the issue dealing with the Trendoids begins with a Chicano low rider, announcing his annoyance about the cultural copycats. The issue then follows the low riders until he meets one of Stewart's teenage assistants, who then takes over the narration. However, while they are both capable of speaking for themselves, neither of them are capable of managing the Mosaic. It is only when John takes over the narration in this sequence, that progress is made. While he still allows others to speak, he selects those from the community that he wants to represent and shows his mastery over them on the next page by sitting on top of the images of those talking.

This formal aspect is reproduced textually in the letter pages of the issue. While it was not unusual for writers to answer fan letters themselves, it was unusual for those letters to be so heavily edited and sandwiched by the author's own words and commentary. Just as Stewart selects those voices which will speak for their respective communities, Jones chooses which letters and what part of the letter to include in his text, while providing commentary on each. Just as Stewart is capable of shaping if not his audience, then at least the perception of his audience.

This formal aspect is reproduced textually in the letter pages of the issue. While it was not unusual for writers to answer fan letters themselves, it was unusual for those letters to be so heavily edited and sandwiched by the author's own words and commentary. Just as Stewart selects those voices which will speak for their respective communities, Jones chooses which letters and what part of the letter to include in his text, while providing commentary on each. Just as Stewart is capable of shaping if not his audience, then at least the perception of his audience.

Early letter pages are filled with fannish questions concerning the limits of John's power ring and demands for favorite characters to appear. As one reformed fan admitted in a later issue, they initially bought "Mosaic for continuity's sake. In other words, I didn't want to miss something in Mosaic that I would need to know in Green Lantern or [Justice League Europe] or whatever." However, as the series progressed more and more fans wrote in either to compare the series favorably to DC Comics more avant-garde Vertigo line or to discuss their own experiences with race vis-a-vis the comic. Although a sure sign of the affective fallacy, these letters nonetheless displayed the transformation of readers who would pick up a title merely for the sure thrills of keeping track of characters and plot threads, to those who were willing to discuss race in a provocative way. Indeed, one of the most interesting facets of the series developed when Jones printed an excerpt from a fan named Shander Tabu Mychal Fullove which accused Stewart of being a traitor to his race, "A man who looked objectively at the decadence and oppression of white society would not stand for its recreation once he has the power to do something about it." He then went on to call John Stewart's white girlfriend a "cave-tramp" and to state in capital letters, "A black man who has grown up under pressures such as John will not be able to settle for anything less than black companionship! Jungle Fever was fiction!" And while this is hardly an enlightened view of race relations in the United States, people angry with Fullove's letter and interested in Jones's request for more letters on the topic of race, were more than happy to write in with more nuanced views.

Early letter pages are filled with fannish questions concerning the limits of John's power ring and demands for favorite characters to appear. As one reformed fan admitted in a later issue, they initially bought "Mosaic for continuity's sake. In other words, I didn't want to miss something in Mosaic that I would need to know in Green Lantern or [Justice League Europe] or whatever." However, as the series progressed more and more fans wrote in either to compare the series favorably to DC Comics more avant-garde Vertigo line or to discuss their own experiences with race vis-a-vis the comic. Although a sure sign of the affective fallacy, these letters nonetheless displayed the transformation of readers who would pick up a title merely for the sure thrills of keeping track of characters and plot threads, to those who were willing to discuss race in a provocative way. Indeed, one of the most interesting facets of the series developed when Jones printed an excerpt from a fan named Shander Tabu Mychal Fullove which accused Stewart of being a traitor to his race, "A man who looked objectively at the decadence and oppression of white society would not stand for its recreation once he has the power to do something about it." He then went on to call John Stewart's white girlfriend a "cave-tramp" and to state in capital letters, "A black man who has grown up under pressures such as John will not be able to settle for anything less than black companionship! Jungle Fever was fiction!" And while this is hardly an enlightened view of race relations in the United States, people angry with Fullove's letter and interested in Jones's request for more letters on the topic of race, were more than happy to write in with more nuanced views.

It is here where the two most interesting failures occur. In creating an audience that would talk about race, Jones had desired to remain authoritarian in his role of author. He would allow for speech, but would be responsible for managing it, much in the same way that Stewart allowed for dissent, but set the parameters and prerogatives for the Mosaic's growth. However, through interacting with fans, Jones was loosing his authorial power as innovating genius. Halfway through the series, the author stopped answering letters directly because as he wrote, "I find arguing with you here every month is threatening to affect the way I write Mosaic stories. . . Not good: the pieces of the mosaic have gotta fall where they gotta fall." Indeed, the critiques of the militant African American woman on screen right now (scroll up) seem to be lifted from that month's printed letter by Fullove. The failure of rhetoric here, and where I believe the series would have developed into a much more interesting document is if the language of the fans could have managed to find its way into the text. This would not have questioned Jones's ability to manage the story, but it would have challenged his desired role of genius.

However, the greatest ethical failure of the series comes not with the cancellation of the title, but the decision to cancel it, and the fear that motivated that cancellation> In this decision, the industry revealed its frailty - a frailty that is disturbing since it seems so many of our popular cinematic myths are now being ripped directly from the comics page. While it is unreasonable to expect editors and publishers like Carlin and Levitz to have the moral courage that Green Lantern showed in running the Mosaic experiment, the retreat that DC management made with so little at stake, betrays a temerity that does raise ethical concerns. Although Jones was clearly creating a series out of artistic self-interest, nevertheless the byproduct was a publication that, although probably never capable of challenging politics en mass, and given the cultural politics of Mosaic's narrative, capital, did seem poised to transform a segment of fandom from Comic Book Guy to politically motivated anti-racist citizen. In the final analysis, the ax dropped on Mosaic shows favor to certain types of safe superhero narratives and denies the validity of a transformation more significant than taking off of one's glasses. Indeed, all it shows is its short sightedness.

However, the greatest ethical failure of the series comes not with the cancellation of the title, but the decision to cancel it, and the fear that motivated that cancellation> In this decision, the industry revealed its frailty - a frailty that is disturbing since it seems so many of our popular cinematic myths are now being ripped directly from the comics page. While it is unreasonable to expect editors and publishers like Carlin and Levitz to have the moral courage that Green Lantern showed in running the Mosaic experiment, the retreat that DC management made with so little at stake, betrays a temerity that does raise ethical concerns. Although Jones was clearly creating a series out of artistic self-interest, nevertheless the byproduct was a publication that, although probably never capable of challenging politics en mass, and given the cultural politics of Mosaic's narrative, capital, did seem poised to transform a segment of fandom from Comic Book Guy to politically motivated anti-racist citizen. In the final analysis, the ax dropped on Mosaic shows favor to certain types of safe superhero narratives and denies the validity of a transformation more significant than taking off of one's glasses. Indeed, all it shows is its short sightedness.

Any typos or grammatical errors are the result of retyping all of this. Any comments that you have regarding content or argument would be loved and cherished.